James Young is a well known name in West Lothian. You can see his name on the back of buses, and there’s James Young High School and James Young House. But what did he do that changed West Lothian?

We, in the UK, use 63 million gallons, or nearly 300 million litres, of oil a day. Just try to picture how many one litre bottles are needed for the year. Most of this is used for transport, both our own cars, heavy lorries bringing us food and things we buy, and air travel moving us around the world. James Young is at the beginning of the oil boom.

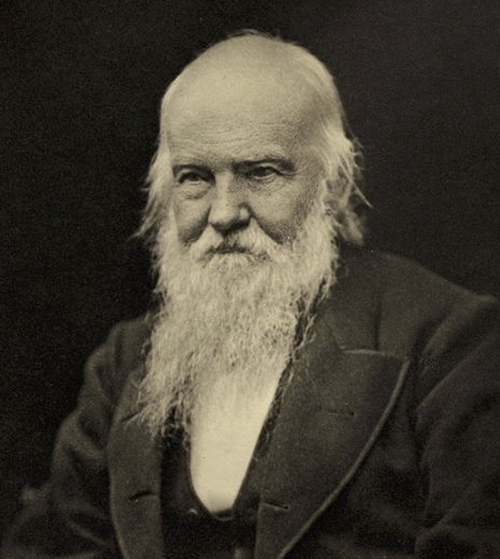

James "Paraffin" Young. Source: Almond Valley Heritage Trust

Oil dripping from the roof

Almost 170 years ago, at a time when the London to Edinburgh west coast line was just completed, coal was the fuel of the industrial revolution. But oil was needed for lighting, and increasingly for industry to keep the machines running. James Young, a chemist working in coal mining, noticed oil dripping from the roof of a coal mine. He thought that there must be a way of producing oil from coal.

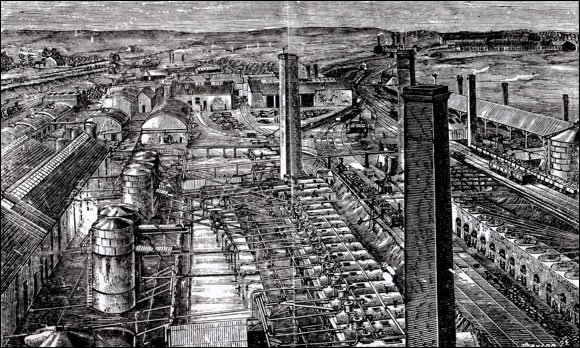

The first commercial oilworks in the world

Young patented his method of heating coal in a retort furnace, using a particular type of coal found in Bathgate, cannel coal, to produce oil vapour, which was collected for refining. The Bathgate Chemical Works was one of the first commercial oilworks in the world. When the supply of cannel coal ran out Young moved to using shale, setting up Addiewell Refinery in 1863. To feed the refinery mining needed to produce a constant supply of oil bearing shale, and coal as well. West Lothian was transformed into a network of mines, railways and villages built to house the people who flooded in to work in the new industry.

A woodcut of Addiewell with the village in the background. Source: Almond Valley Heritage Trust

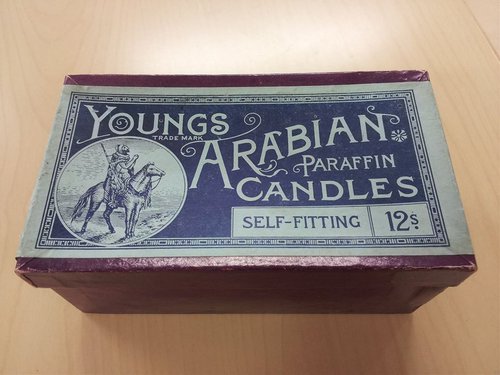

Paraffin, candles and petrol

At the start Young’s refinery produced oil for lighting, and also developed new types of light which gave better light. This was much better and cheaper than whale oil, and burnt cleaner. But the increasing popularity of cars meant that the West Lothian refineries produced petrol and diesel fuel. Paraffin wax was used to make candles, and a by-product of the retort process was ammonium sulphate fertiliser.

A box of Young's candles. Source: Almond Valley Heritage Trust

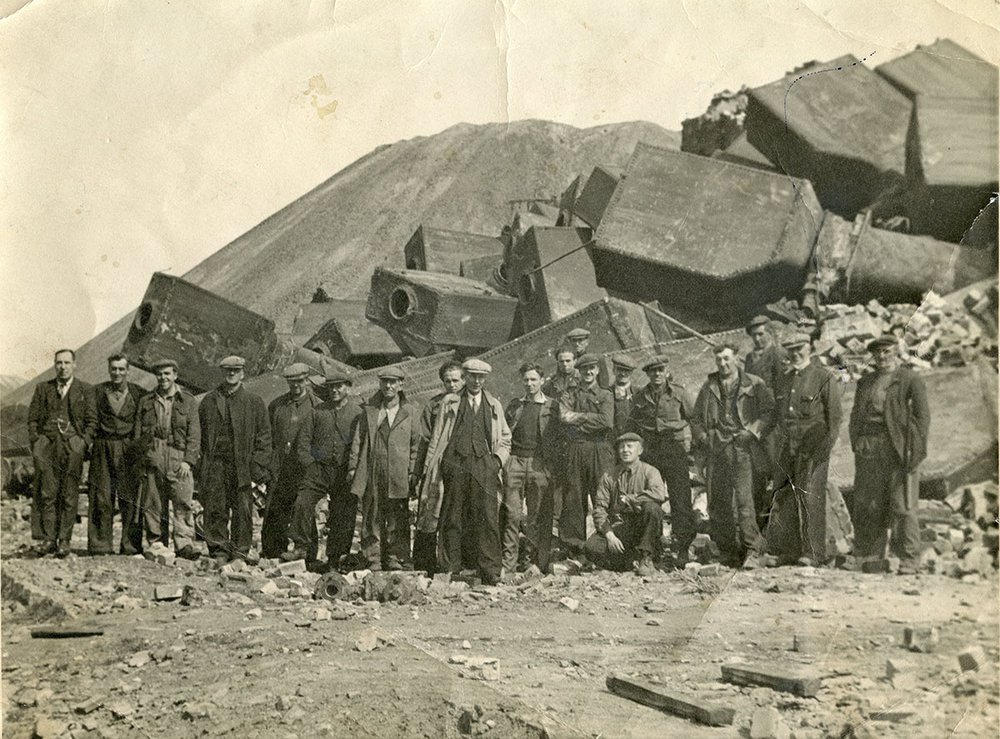

A slow decline

The early twentieth century was when Scottish oil production was at its highest, employing over 12 000 people. But competition from American and later Middle Eastern oilfields was a problem as it was cheaper to import oil. Grangemouth refinery opened in 1924, using expertise developed in shale oil refineries, to process imported oil. The industry contracted in the 1920s, revived before the Second World War to protect oil supplies, and eventually closed completely in the 1960s.

The end of an era, few of the structures of the industry remain.

Demolition of Hopeton Oilworks c1958. Source : Almond Valley Heritage Trust