The shale oil industry shaped West Lothian as it is today. But without people coming to work in the mines, pits and oil works there would have been no oil boom.

"In the course of less than half a century, West Lothian was transformed from a small, rural, homogenous population to a growing multi-ethnic one." Sybil Cavanagh 1992

The Pull of a Better Life

Just over another half century ago the shale industry closed down, leaving behind mountains of red waste, lost villages and acres of derelict land needing restoration. It also left a changed population of communities that were created through changes in technology and having to adapt to new changes and structures. If you live in West Lothian now, and have an Irish surname, or one that originates in the Highlands then there’s a good chance that your ancestors migrated to work in the oil works. We tend to view nineteenth century communities as settled and static, tied to a place and the land. The mid 1800s were a time of great change, and what pushed people to move to West Lothian were the same things that cause people to move today.

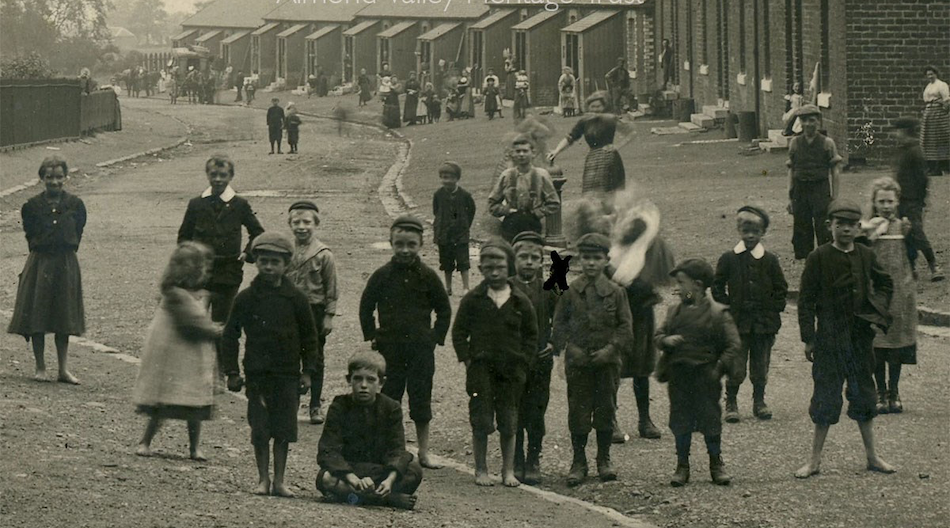

Unknown miners, West Lothian. Source: Almond Valley Heritage Trust

Irish Family evicted by their landlord c1879. Source: Wikimedia Commons

The Push of Destitution

What would make you swap the clean open air for dark, dangerous work down mines, or in the heat, smoke and fumes of the oil refinery? Work, or the lack of it; starvation; poor housing and living conditions all meant that there was a ready work force for the shale mining and refining. The potato blight caused famine in Ireland and the Highlands. In Ireland starvation and emigration reduced the population by a quarter. The collapse of the clan system, agricultural changes and the resulting clearances were forcing Highlanders to emigrate. The chance of work, any work, would be a big attraction.

People, Places and Memory

The legacy of this movement of people is visible across West Lothian. You can see it in the surviving housing built for shale workers such as the miners’ rows in Winchburgh and Broxburn. Much of the shale housing was demolished in the 1950s and 1960s. It is present in the Catholic churches and schools spread across what was a very Presbyterian region. It is there in the place names and street names. It is in the miner’s institutes and the West Calder Co-op, people helping themselves.

But as Alistair Findlay asserts in ‘Shale Voices’, ‘a community exists in its anecdotes’, in the stories that are told about work, place and locality. The physical remains are visible and these are a way of reaching the memories and the stories that connect West Lothian to its history.

Broxburn Primary School 2019. Source: Written in Film